Political opinions have always been one of the most socially unifying or divisive topics, defining the people we surround ourselves with. It has been intensely debated the extent to which contemporary political parties well represent each ideology and their internal and temporal coherence of opinions. In the following paragraphs, we will investigate how such opinions and ideas can influence the way politicians speak, what they talk about, and the way they do it, with the ultimate aim of predicting the party of a politician just by his sentences, without any prior knowledge on the speaker. Is that possible? A machine learning classifier will try to answer this question.

What and where: the two giants

Let’s start from the beginning. Since trying to answer the previous questions on a global scale would be too big of research for a single story, we decided to focus on the two most famous political parties in the world: USA’s Republican and Democratic parties.

Even if you are not living in the United States, you are probably flooded by news about these two parties almost every day, wherever in the world you live. This is because the USA is one of the most powerful countries globally, and its electoral system is a two-party system. That means that two parties - namely the Republican Party and the Democratic Party - dominate the political field in all three levels of government. Other parties, often generally termed “third parties” in the U.S., include The Green Party, Libertarians, Constitution Party, and Natural Law Party; however, we will not focus on them in this research.

If you’re not fond of politics and don’t know much about the Republicans and the Democrats, here are some insights about them from Wikipedia.

The Republican Party, also referred to as the GOP (“Grand Old Party”), was founded in 1854. Its 21st-century ideology is American conservatism, which incorporates social and fiscal conservatism. The GOP supports lower taxes, free-market capitalism, restrictions on immigration, increased military spending, gun rights, restrictions on abortion, deregulation, and labor unions. In the 21st century, the demographic base skews toward men, people living in rural areas, members of the Silent Generation, and white Americans, mainly white evangelical Christians. Its most recent presidential nominee was Donald Trump.

The Democratic was founded around 1828. Its philosophy of modern liberalism blends notions of civil liberty and social equality with support for a mixed economy. Corporate governance reform, environmental protection, support for organized labor, expansion of social programs, affordable college tuition, health care reform, equal opportunity, and consumer protection form the core of the party’s economic agenda. On social issues, it advocates campaign finance reform, LGBT rights, criminal justice, and immigration reform, stricter gun laws, abortion rights, the abolition of capital punishment, and the legalization of marijuana. The current president, Joe Biden, is a Democrat.

How: the datasets that helped us with this data story

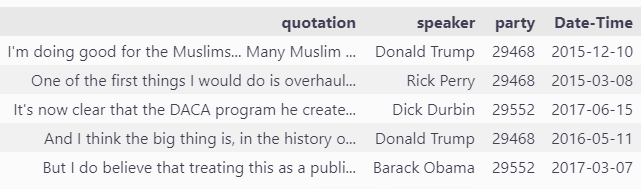

To learn meaningful insights about sentences from politicians, we first needed the sentences. That’s where came into play the Quotebank dataset, an open corpus of 178 million quotations attributed to the speakers who uttered them, extracted from 162 million English news articles published between 2008 and 2020.

We made use of information available from Wikidata to extract information about the political affiliation of the speakers. We extracted a subset of quotes where the speaker was a member of the Republican or the Democratic party, filtering out speakers who have never run for any state or federal level election. Most of the speakers affiliated with the political parties were not actual politicians but celebrities, sports stars, TV personalities, etc. We believe it was beneficial only to take the real politicians, as they are more likely to speak about actual political matters and represent their party’s ideology. Such filtering and processing resulted in a dataset of 1.6 million quotations from American politicians.

Below, you can see a couple of sample quotations from the dataset and a plot of the distribution of quotations from 2015 to 2020.

A deep dive into the data: what are the trending topics?

Previous to any more profound analysis, the most important thing we could do was understand what the two parties talked about. What are the main problems, topics, trends, and events of the United States? How do politicians address them? First, let’s look at the “big words”, those words that are always used and that you will most likely run into if you’re reading a sentence told by whatever politician.

Then, we try to look for a difference between the two parties. We divide the quotes into two groups based on the party affiliation of the speaker. Then we take the 500 most common words from the first wordcloud, and compare their frequencies between the parties. We divide the per-party word frequencies by the global word frequencies to obtain the relative frequencies per party. We then plot two new wordclouds, now using the relative frequenies instead of total word counts as the weights.

The wordclouds clearly visualize the difference in the vocabulary used by the members of the two American parties.

In the Democratic wordcloud, we can see that:

- terms related to the main ideology of the party

democraticanddemocracyappear quite commonly - words like

climate,affordable,education,college,medicareandcommunitiespoint towards important topics for the Democratic party - presence of words like

challenge,responsibilityoraccountableshowing initiative to point out issues with the current situation

On the other side, in the Republican wordcloud we can observe:

- presence of words like

horribleandtremendous, which were very frequently used by President Donald Trump mexicois quite a popular topic, likely because of the Republican administration attitude towards the Mexican border and the plans of building a wall- a lot of terms related to international politics: country names including

canada,saudi,china,koreaandrussia

Identifying the most commonly used words is an excellent first step to understanding what politicians often talk about, and we can already spot some differences between the two parties. Still, the results are a bit too fine-grained to draw meaningful conclusions from them. To overcome this issue, we want to identify the high-level concepts commonly discussed and classify each quote into one of them.

To achieve that, we first tried to use a transfer-learning approach: train a classifier on the data obtained from the Manifesto-Project dataset, which provides sentences of the two parties’ manifestos over the years 2012, 2016, and 2020, labeled manually by experts to one of fifteen different topics/categories. Unfortunately, the data was too different from ours, and thus the resulting accuracy was not satisfying.

We then proceeded with unsupervised clustering using BERTopic. This topic modeling technique leverages transformers and c-TF-IDF to create dense clusters allowing for easily interpretable topics while keeping essential words in the topic descriptions.

The following plot summarizes the interesting results we obtained from clustering.

The first thing worth noting from the stacked plot is the x-axis, reporting the macro-topics. Since this is the result of unsupervised clustering, those are the most frequent themes covered by representatives in their speeches. In the overall top 3, we have racial discrimination, nuclear weapons, and Russiagate.

However, what is much more interesting is the difference in the most critical talking points between the two parties. Democrats put racial discrimination first, whereas Republicans talked more than everything else about Russiagate. Trying to explain why that is and the social reasons behind such differences is probably incredibly hard and out of the target of this data story. For this reason, we try to explain the top topic of Democrats as superficial proof of the validity of our findings. Why racial discrimination is a central theme of discussion needs probably no explanation, especially given the 2020 events, but why Democrats talk more about it might be explained by this plot taken from Pew Research Center’s research.

Such finding shows that Democrats are more willing to change things to give blacks equal rights with whites; therefore, it makes sense that their politicians speak more about the problem.

Let’s now see things more in detail, looking at the top 10 topics from the two parties during the years.

First, we notice a spike in the Nuclear Weapons topics in 2015 on the Democrat side, likely referring to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the nuclear deal with Iran, which Obama helped negotiate. As expected, in the following year, we see the rise of Hillary Clinton due to the 2016 presidential election. Insight of that, Republicans talked more about immigration from the Mexican Border (we remember Trump’s wall on the Mexican border was a strong point in his campaign). At the same time, Democrats seemed more focused on Racial Discrimination and the middle east (ISIS and Israel). By the end of the year, we see the rise of what would become the most talked about the following year, the controversial RussiaGate(Special Counsel investigation). This was an investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections, links between associates of Donald Trump and Russian officials, and possible obstruction of justice by Trump and his associates. From 2017 we also notice North Korea, which reminds us of the conflict between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un and their trade of insults over the web. Furthermore, in 2017 the Atlantic hurricane season was an extremely active one and the costliest on record, with a damage total of at least $294.92 billion, in line with what’s shown in the plot. Then, in 2019, as the RussiaGate started to quieten, another conflicting topic rose: Black Lives Matter, as testified by the topic Racial Discrimination. While it is a predominant topic in democrats’ quotes, we can see that the Republicans tended to overlook it. Finally, in 2020, we witnessed the outbreak of the covid epidemic (Healthcare topic).

How do Democrats and Republicans relate to national and international problems?

People say that how you relate to an obstacle has a significant impact on how you try to solve the obstacle itself. Even though that’s often said about the individual’s way of solving problems, it’s essential to see how political parties approach different issues to understand further the data we have seen so far.

Having identified the topics often discussed by politicians, it is interesting to also identify their attitude towards those topics and identify whether it depends on a politician’s affiliation.

To achieve that, we will make use of two sentiment analysis tools:

VADER-Sentimentlibrary: a rule-based sentiment analysis tool- HuggingFace

transformerslibrary: a deep-learning-based NLP library providing access to several state-of-the-art models, often pre-trained on large datasets. In particular, we will use this RoBERTa model for pre-trained specifically for the sentiment analysis task.

Both tools will assign to a sentence a score between -1 and 1, where -1 means a highly negative sentiment, whereas +1 means a highly positive one. A score of 0 represents neutrality. Let’s first have a look at the global sentiment distributions that the models produced:

The two distributions are very different from each other. The sentiment predicted by VADER has a large peak around the 0 mark, which means that it struggled to attribute any kind of sentiment to a large portion of the quotations. Apart from the peak, the distribution looks like a sum of two normal distributions with means of 0.5 and -0.5. The sentiment predicted by RoBERTa follows an almost uniform distribution, but the negative values appear more frequently and there are visible peaks at [-1, 0, 1]. Let’s now take a look at the sentiment distributions per party (excluding the zero-sentiment quotes from VADER):

The results are similar for both parties, but not totally identical. On average the Democrats’ quotations have a slightly more positive sentiment than those of the Republicans. A t-test shows that the gap in the means is statistically significant, returning p-value < 1e-200 for both RoBERTa and VADER distributions. Another interesting observation is that the Republicans tend to have more highly positive (> 0.5) and highly negative ( < -0.5) quotes. This is especially visible in the RoBERTa plot - we see clear peaks on the left and right ends of the distribution. Gustave Le Bon shows in “The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Minds” that emotions play a crucial role in mass communication and from our analysis it seems that the Republican politicians share his point of view.

Despite the differences, there’s no substantial gap in the results when looking at the global sentiment distributions of the two parties. Investigating further details, we then looked for sentiments at the topic level.

Before proceeding, we would like to clarify a possible misunderstanding of the results. Suppose, for example, we see a predominant negative sentiment over the topic of education. In that case, that doesn’t mean that politicians are against it, but rather that when they talk about it they usually have some criticism. To be more specific, if a speaker is complaining about the educational system and wants to suggest some improvements, they would probably use some negative sentiment in their words, but that wouldn’t mean that they are against education itself.

Let’s move on to the actual results of the analysis. We will focus on the RoBERTa sentiment analysis, as the VADER results contain much more 0-sentiment predictions which makes them less interesting for performing a per-party comparison. Sentiment per topic is visualized below:

What can we see? Firstly, we can notice how negative sentiment exceeds positive: one reason for this might be that quotes are taken from news articles, which usually talk more about problems than positive events, just because they sell better.

Then, let’s take a look at the most negative topics for both parties. It is interesting to see that fake news takes the lead over terrorism in that category - is it a hint that it might be one of the biggest threats of the coming years? politics also is among the topics with the most negative sentiment - quite ironic considering that all the evaluated quotations come from politicians…

Among the topics with the most positive sentiment we see traditional values - this can be an indication that even if politicians do not necessarily support all the traditional values, it still is quite a bold move to publicly criticize them.

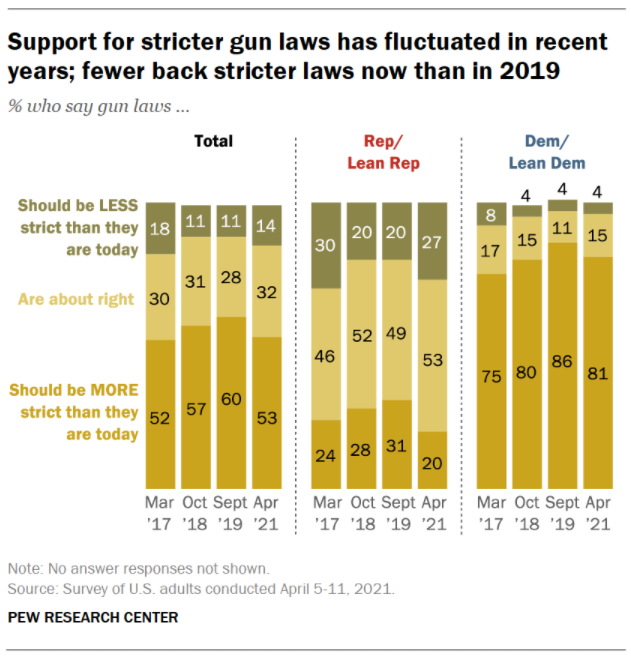

Looking for topics with remarkable differences in sentiment across parties, we see how the Democrats tend to have a more negative attitude towards the guns topic than the Republicans. As stated before, this does not necessarily mean that Democrats are against guns, but making stricter rules on guns is part of their campaign, so we can infer that, and other studies confirm it also about their supporters.

Democrats used much more positive sentiment than Republicans when considering topics such as Hilary Clinton, Obama, Joe Biden, and the Democratic Party which also matches the expectations. A significant gap between the two parties can be also observed in the ‘taxes’ topic. However, in this case, results might be quite counterintuitive: one might have expected Republicans to have a more negative approach towards taxes as lower are among their primary postulates, but in our analysis Democrats were the ones with a stronger negative sentiment towards the topic of taxation.

What is the complexity and general understandability of the parties’ sentence?

The final aspect we decided to analyze is how the two different parties speak to their supporters. Since one of the pillars of rhetoric is that you should adapt your speech based on the people who will listen to it, we thought it would be fascinating to see the differences we can find.

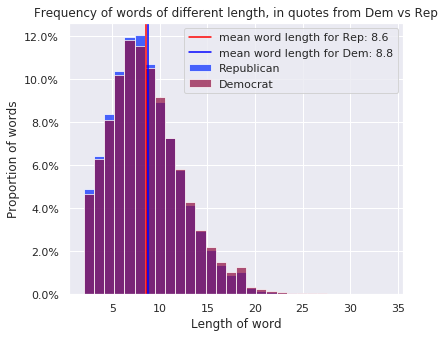

Let’s start with the different lexicon used. The first analysis we did was on the distribution of words length.

As we can see, the difference is almost none. Still, there’s a statistically significant difference between the two average lengths of words in quotes from Republican vs. Democratic speakers (p-value of ~0.0). This might suggest the use of slightly more complex words by Democratics, assuming that a longer-term is also more complex.

A sentence is not just about the words in it, but how they’re put together as well. For this reason, we then moved our attention to some metrics that are used to measure the grammatical complexity of quotes:

- Flesch reading ease: in the Flesch reading ease test, higher scores indicate material that is easier to read; lower numbers mark passages that are more difficult to read.

- Dale Chall readability score: different from other tests since it uses a lookup table of the most commonly used 3000 English words. It returns the grade level necessary to understand the sentence. Hence, the higher the score, the higher is the difficulty.

- Text Standard: based upon a combination of all the library’s tests, returns the estimated school grade level required to understand the text.

- Reading time: returns the reading time of the given text—Assumes 14.69ms per character.

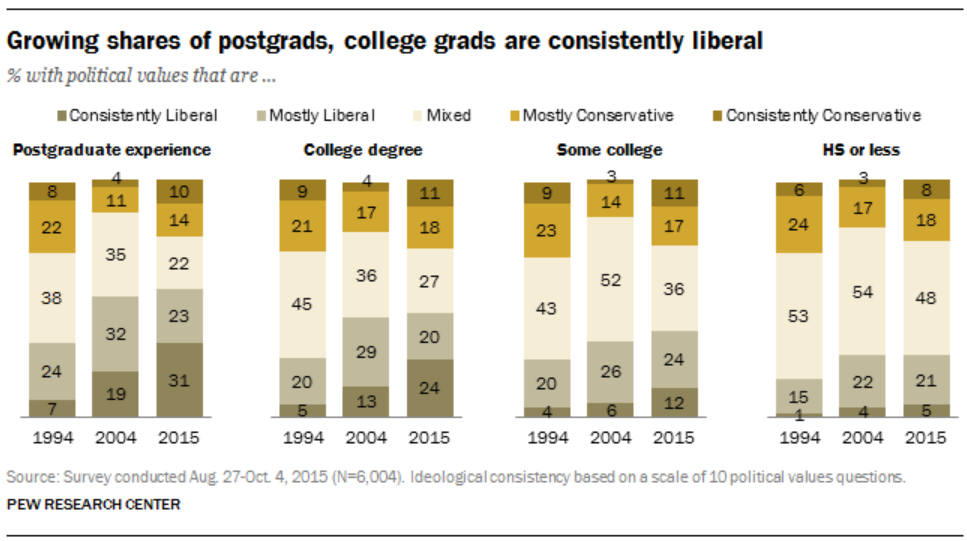

The result is stable across years and metrics. It seems to suggest just one thing: there’s a substantial difference in the complexity and readability of quotes from the two parties, and usually, Republican ones are easier to understand, as well as faster to read, even though reading time shows the smallest gap of the four metrics. We then repeated the same analysis but just to Barack Obama and Donal Trump’s quotes, the two most popular speakers from the two parties. What we obtained were exactly the same results. Does this outcome make sense? Many articles covered this topic and what turned out to be transparent in all of them is that Republicans and Democrats have become more and more polarized, with entirely different opinions and languages ( Why Democrats and Republicans Speak Different Languages. LIterally. - The Atlantic, Democrats and Republicans No Longer Speak the Same Language - The New York Times, Why Democrats and Republicans Use Different Words - Business Insider).

Considering all this, we should probably have not expected anything else but a significant gap. Why though Democrats use more complex sentences? Getting back to the rhetoric principle that a speaker adapts to his supporters, does this suggest that Republicans’ defenders are less literate? Accordingly to this plot and this research from Pew Research Center, yes.

Pulling all together: creating the final party classifier.

After all this analysis, it’s time for us to answer our question: can a bunch of words tell what your political view is?

For this purpose, we put together information about topics, sentence complexity scores, and sentiment evaluation from both VADER and RoBERTa tools and used them to construct a training dataset. We performed rebalancing of the dataset, to ensure that there are equally many examples for Democratic and Republican quotations in the dataset. We split the dataset into training and test sets and we used the first part for training a simple party classifier using Linear Regression. From such a model, we obtained that all features have a statistically significant correlation with the outcome; hence all the data gathered from our analysis will help us predict the correct party. When using the model to predict on an unseen test set, we get an accuracy of 0.64.

Given the results, we can conclude that despite various differences in approaches of the parties to the different topics and the difference in language complexity at a macro level, that information is not sufficient to precisely determine the speaker’s affiliation given a single quotation. However, you can predict it with a probability significantly better than random (in almost two thirds of the cases), and quite likely that when given a larger text-corpus from one speaker you could predict their affiliation with a higher accuracy. Additionaly, for this classifier we have not been using the actual text contained in the quotations, but just the metadata generated in the previous analyses. Using the actual text and training a state-of-the-art deep learning model such a fine-tuned BERT model or an LSTM using Word2Vec embeddings one can expect even better results, as those can capture more information than our simple classifier.

Conclusion

In this datastory, we presented an extensive analysis on a dataset of quotations of American politicians. We performed quantitative word frequency analysis and used unsupervised learning techniques to discover clusters corresponding to topics commonly covered in the quotations. We analyzed the sentiment both at a global and per-topic level. We performed lexical complexity analysis of the quotations. At all of these stages we pointed out the differences between the Republicans and the Democrats. Finally, we proposed a simple clasasifier to try to predict speaker’s political affiliation based on quotation features such as complexity, topic, date and sentiment.

.png)